By Laura Karppinen, Member of the Finnbrit Social Committee

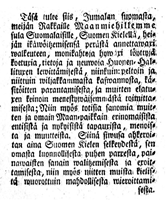

“Täsä tulee siis , Jumalan suomasta meijän Rakkaille Maanmiehillemme sula Suomalaisille , Suomen Kielellä , heijän ikäwöitzemisensä perästä annettawaxi walkeuteen , monikahtoja hywäxi löyttyjä koetuxia , tietoja ja neuwoja Huonen-Hallituxen lewittämisestä , niinkuin : peltoin ja niittuin wiljakkammasta kaswannosta , käsitöitten parantamisesta , ja muitten elatuxen keinoin menestywäisemmästä toimittamisesta ; Niin myös totisia sanomia muitten ja omain Maan-paikkain erinomaisista entisistä ja nykyisistä tapauxista , menoista ja muutteista.”

Laura Karppinen talked about the life of Anders Lizelius in an online event on the 11th of February 2022. Laura described Lizelius as a practical man, a devout Christian, and a man who made things happen. “I am much impressed by his example in many ways.”

In short, Lizelius reformed funding of the poor by helping to remove the need for begging by introducing “poorhouses” and laying the foundations for the creation of the Finnish welfare state. He translated the Old and New Testaments, created new words in Finnish, and improved the development of Finnish grammar. He was also the founder of the first Finnish newspaper and thereby, secular literature in Finnish.

And yet – very few of us have heard of a person called Anders Lizelius! He was born in 1708, with his childhood marred by the Great Northern War – when Finland was occupied by Russia. Lizelius was the son of a peasant and spoke Finnish as his mother tongue. He only started school at the age of 16 and was 22 when he began studying at University.

The Use of Finnish when Lizelius was a Student

Turku was still a very small provincial town. University studies were in Latin, but Swedish was being introduced, as a great novelty. The general permission to use Swedish in academia was granted from 1752 onwards. Classical studies were also giving way to science and practical studies such as agriculture, as an effect of the Enlightenment and the loss of Sweden’s status as a great power.

Finnish had no status in public, non-religious matters. Those were conducted in Swedish. In religious matters, Finnish had a strong status because of the Evangelical Lutheran principle that everyone ought to receive God’s word in their own language. This also led to the principle that everyone ought to be able to read God’s word (Bible, hymn book, catechism).

Estimates vary but approximately 50 to 80 % of the population were able to read in the mid-18th century. In principle, one had to be able to read to be confirmed, which again was a prerequisite for getting married, so there was a strong incentive. Children were taught by parish clerks in parish villages, or by trusted literate persons in more remote places.

There were no books at all in Finnish except the religious ones. The only other published texts in Finnish were some edifying texts in Almanacs. There was a movement in academia called Fennophiles (Friends of Finland and Finnish); this movement wished to advance and study Finnish culture and language – it had no political goals.

One Job Led to Another – from a Rector to Translation

Lizelius became Rector of Pöytyä, in Varsinais-Suomi (Finland Proper) in 1739, through conservation of his predecessor’s daughter (a common practice in those days: the living was given to the candidate who married the predecessor’s widow or daughter, thereby “conserving” the family) Lizelius was 31 years old.

Lizelius started keeping minutes of the parish assembly in Finnish in 1756. As the first one in Finland; it took 100 years for the practice to become mandatory. He had to develop numerous words into the Finnish language to be able to do this, e.g. “lahjoitus” (donation), “kunta” (municipality), “pykälä” (paragraph), vuosisata” (century); even ”kirkonkokous” (parish assembly).

The first Bible entirely in Finnish was published in 1642 and a new edition in 1685. In the mid-18th century, the editions were sold out and a new revised edition was needed. The chapter asked the clergy for comments and suggestions, such as observed errors in translation, for the new edition. Lizelius was the only one to comment and suggest but his input was profound and extensive. The chapter nominated Lizelius as the translator-editor. His task included correcting the translation, correcting misprints, and thoroughly revising the Finnish language used. Lizelius did his work based on both the Bible in the original languages and, for comparison, the Latin, German, Swedish, and Danish translations.

The translation/editing work corresponded with emerging academic work on understanding Finnish. The vocabulary was considerably Finnicized, e.g., “krantsi” > “seppele”; “myntätä” > “lyödä rahaa”. Grammar was developed, and the spelling was brought nearer to the spoken language. Also at that time, the first grammar was published where Finnish was not forcibly moulded into the shape of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and the first collections on folklore etc. began.

First Steps in Care of the Poor – Setting the Foundation for the Finnish Welfare State

Care of the poor was based on allotments: the poor were allotted to certain households and were rotating between these. Those who weren’t given an allotment did the rounds as beggars.

Lizelius introduced a poorhouse, and even more significantly, the building of a loan granary. This granary is still in existence. The principle was that a collection for the poor was taken every Sunday, the money was used to purchase grain to the granary, the grain was lent on interest, and the interest was used to maintain the poorhouse. In addition, the granary was useful in preventing farms from falling into the hand of usurpers in tougher years.

Lizelius’ relief programme was simple: The poor are ordained by God. Therefore, the duty of relieving the poor is also ordained by God. God promises his mercy and blessing to those who relieve the poor. God promises equally his wrath and punishment to those who neglect the poor.

In 1761, at the age of 53, Lizelius became Rector of Mynämäki parish. His wife died after giving birth to their 13th child and a year later he married a childless widow.

In Mynämäki, Lizelius entirely reformed relief for the poor. In addition to having the poorhouse and loan granary built, he got the parish assembly to accept that every household paid a certain amount of grain and pulses for the relief, which was distributed to the poor, both in the poorhouse and outside it. As a result, beggary was entirely stopped.

The Work on Developing the Finnish Language Continues

The 1758 edition of the Bible was sold out in a few years. Basically, for 15 years there was no Finnish Bible, the only comprehensive book in Finnish, available. The chapter granted the privilege of printing the new edition to the Frenckell printing house. Because of business conflicts, Bible printing took years and years.

Lizelius was again nominated as editor, but this time his orders were strictly just to correct misprints. He cautiously enlarged his mandate towards also developing the Finnish language further; his goal was to make the Bible a model work of Finnish.

The most tangible result was substituting c with k and even otherwise further improving the spelling. This edition of the Bible, “The Old Church Bible”, was used in the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran church until the 1930s. Some revivalist movements, like Prayerism, still use it.

Publisher of the First Finnish Newspaper

The first newspaper in Finland was the Swedish-language Åbo Tidningar in 1770. It was, obviously, directed to the educated classes. There were ca 150 to 200 subscribers. This paper inspired Lizelius to the even bolder step of starting to publish a paper in Finnish, directed to the Finnish-speaking people, that is, to the common people. This was in 1775. This makes him the founder of secular literature in Finnish.

The newspaper included useful economic information such as animal husbandry, farming, home medicine, Finnish and foreign history and news, and of course, the development of the Finnish language. There was much instruction on the care of accidents and infectious diseases. Also, advice on the advanced rotation of crops, hay cultivation etc. that was so ahead of its time that it had little practical significance.

Most foreign news articles were copied from Swedish papers. To facilitate understanding the news, there was a series of articles on world geography. This shows the paper’s lofty aims not just to give practical information but to educate and edify, e.g. knowing about the American Revolutionary war could not be of practical use to farmers.

Sadly, the low demand caused by both universal poverty and inexperience in reading anything bar religious texts caused the newspaper to be given up in little more than a year.

Lizelius’ spirit lives on and work continues developing the Finnish language and social security in Finland. Words such as “villiruoka”, “överi”, “mikroilme”, “lähimaksu”, “ääniviesti” “jenkkakahva” and “resilienssi” were added to the Finnish dictionary recently. And of course, arguably the biggest reform of social security and the health sector (SOTE renewal) is being implemented as we speak!